Why is custom casting the preferred choice for complex structural components over welding or machining?

Release Time : 2025-12-31

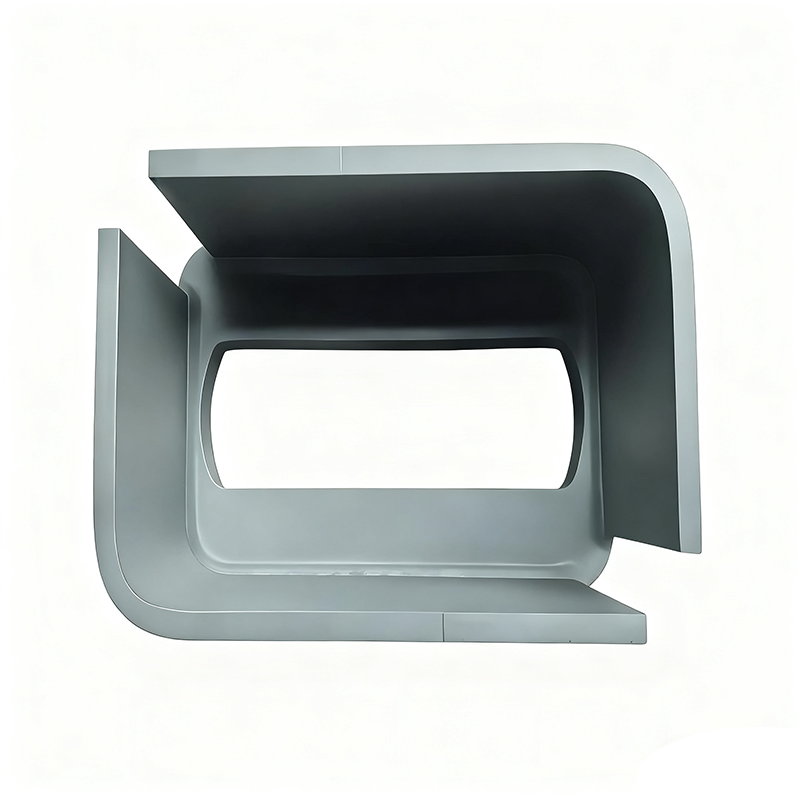

In heavy machinery, energy equipment, rail transportation, and even precision industrial equipment, many critical components often possess irregular curved surfaces, internal cavities, multi-directional branches, or alternating thicknesses. Considering performance, cost, and reliability, custom casting is becoming the preferred path for complex structural components—it's not just a forming method, but a system-level engineering wisdom.

First, casting achieves near-net-shape forming, preserving material integrity to the maximum extent. While welding can assemble simple parts, the weld area inevitably contains a heat-affected zone with different microstructure and properties from the base material, easily becoming stress concentration points or corrosion weak points. Furthermore, if large castings are made from multiple welded sections, the more joints there are, the higher the potential failure risk. In contrast, custom casting, through a single pour, allows the metal to solidify naturally in the mold, forming a continuous, dense internal structure without welds or splices, resulting in uniform overall mechanical properties. This "one-piece molding" advantage is particularly crucial for components subjected to alternating loads or high-pressure environments.

Secondly, casting grants unprecedented design freedom. Machining relies on tool accessibility and is often helpless with structures such as deep cavities, recesses, and intersecting channels, sometimes even requiring disassembly into multiple parts and reassembly, significantly increasing complexity. Casting, however, is virtually unrestricted by geometry—if the mold can be made, the metal can be filled. Whether it's the complex flow channels of turbine blades, the helical cavities of pump housings, or the multi-directional reinforcing ribs of support components, casting can accurately reproduce them. This "what you imagine is what you get" capability allows designers to break free from process constraints and focus on functional optimization, thereby fostering more efficient, lighter, and more integrated product structures.

Furthermore, it offers high material utilization, significantly reducing manufacturing costs and resource waste. Machining large, complex parts often requires cutting from a solid blank several times its volume, resulting in a large amount of metal becoming waste; while casting directly shapes the final contour, leaving only a small allowance for finishing, resulting in extremely low material loss. This advantage is even more pronounced for expensive alloys (such as special cast steel and nickel-based alloys). Meanwhile, eliminating multiple welding, straightening, and flaw detection processes shortens the production cycle and reduces labor and energy consumption.

Furthermore, casting technology is mature and controllable, with continuously improving quality stability. Modern casting is no longer synonymous with "extensive" or "inefficient." By simulating the solidification process using computer simulations, optimizing gating systems, and employing high-precision sand or metal molds, coupled with strict melting control and heat treatment procedures, defects such as porosity, shrinkage, and cracks can be effectively suppressed. Combined with non-destructive testing methods, this ensures that every custom casting possesses reliable internal quality and consistent mechanical properties. This "controllable complexity" is precisely the core capability relied upon by high-end manufacturing.

At a deeper level, choosing casting is an investment in the reliability of the product throughout its entire lifecycle. A welded structure may experience fatigue cracking under long-term vibration, while a monolithic casting can more evenly distribute stress; a machined assembly may deform at high temperatures due to differences in the coefficients of thermal expansion of different materials, while a single-material casting maintains dimensional stability. In critical areas concerning safety and durability, this inherent consistency is irreplaceable.

Ultimately, the preference for custom casting for complex structural components is not outdated, but based on a profound understanding of the nature of materials, structural logic, and manufacturing philosophy. It uses the flow of liquid metal to transform complexity into a unified whole; it uses the wisdom of one-time molding to minimize risk. When the base of a large wind turbine stands as stable as a rock, when the propeller of a ship cuts through the waves, custom casting often silently supports it—bearing immense weight with a unified form. True manufacturing art lies not in showing off techniques, but in perfectly shaping materials to become what they are meant to be.

First, casting achieves near-net-shape forming, preserving material integrity to the maximum extent. While welding can assemble simple parts, the weld area inevitably contains a heat-affected zone with different microstructure and properties from the base material, easily becoming stress concentration points or corrosion weak points. Furthermore, if large castings are made from multiple welded sections, the more joints there are, the higher the potential failure risk. In contrast, custom casting, through a single pour, allows the metal to solidify naturally in the mold, forming a continuous, dense internal structure without welds or splices, resulting in uniform overall mechanical properties. This "one-piece molding" advantage is particularly crucial for components subjected to alternating loads or high-pressure environments.

Secondly, casting grants unprecedented design freedom. Machining relies on tool accessibility and is often helpless with structures such as deep cavities, recesses, and intersecting channels, sometimes even requiring disassembly into multiple parts and reassembly, significantly increasing complexity. Casting, however, is virtually unrestricted by geometry—if the mold can be made, the metal can be filled. Whether it's the complex flow channels of turbine blades, the helical cavities of pump housings, or the multi-directional reinforcing ribs of support components, casting can accurately reproduce them. This "what you imagine is what you get" capability allows designers to break free from process constraints and focus on functional optimization, thereby fostering more efficient, lighter, and more integrated product structures.

Furthermore, it offers high material utilization, significantly reducing manufacturing costs and resource waste. Machining large, complex parts often requires cutting from a solid blank several times its volume, resulting in a large amount of metal becoming waste; while casting directly shapes the final contour, leaving only a small allowance for finishing, resulting in extremely low material loss. This advantage is even more pronounced for expensive alloys (such as special cast steel and nickel-based alloys). Meanwhile, eliminating multiple welding, straightening, and flaw detection processes shortens the production cycle and reduces labor and energy consumption.

Furthermore, casting technology is mature and controllable, with continuously improving quality stability. Modern casting is no longer synonymous with "extensive" or "inefficient." By simulating the solidification process using computer simulations, optimizing gating systems, and employing high-precision sand or metal molds, coupled with strict melting control and heat treatment procedures, defects such as porosity, shrinkage, and cracks can be effectively suppressed. Combined with non-destructive testing methods, this ensures that every custom casting possesses reliable internal quality and consistent mechanical properties. This "controllable complexity" is precisely the core capability relied upon by high-end manufacturing.

At a deeper level, choosing casting is an investment in the reliability of the product throughout its entire lifecycle. A welded structure may experience fatigue cracking under long-term vibration, while a monolithic casting can more evenly distribute stress; a machined assembly may deform at high temperatures due to differences in the coefficients of thermal expansion of different materials, while a single-material casting maintains dimensional stability. In critical areas concerning safety and durability, this inherent consistency is irreplaceable.

Ultimately, the preference for custom casting for complex structural components is not outdated, but based on a profound understanding of the nature of materials, structural logic, and manufacturing philosophy. It uses the flow of liquid metal to transform complexity into a unified whole; it uses the wisdom of one-time molding to minimize risk. When the base of a large wind turbine stands as stable as a rock, when the propeller of a ship cuts through the waves, custom casting often silently supports it—bearing immense weight with a unified form. True manufacturing art lies not in showing off techniques, but in perfectly shaping materials to become what they are meant to be.